Better Smut by Hand • Wednesday Black

Bretty Rawson

Publishing under a nom de plume, this rising novelist reflects on how writing the first draft of her erotic novella by hand led to all kinds of unforgettable feelings.

Read MoreSince we aren't on every social media site, let us come to you. Enter your email below and we'll send you our monthly handwritten newsletter. It will be written during the hours of moonrise, and include featured posts, wild tangents, and rowdy stick figures.

Keep the beautiful pen busy.

Brooklyn, NY

USA

Handwritten is a place and space for pen and paper. We showcase things in handwriting, but also on handwriting. And so, you'll see dated letters and distant postcards alongside recent studies and typed stories.

search for me

Publishing under a nom de plume, this rising novelist reflects on how writing the first draft of her erotic novella by hand led to all kinds of unforgettable feelings.

Read More

HANDWRITTEN BY TRINITY TIBE

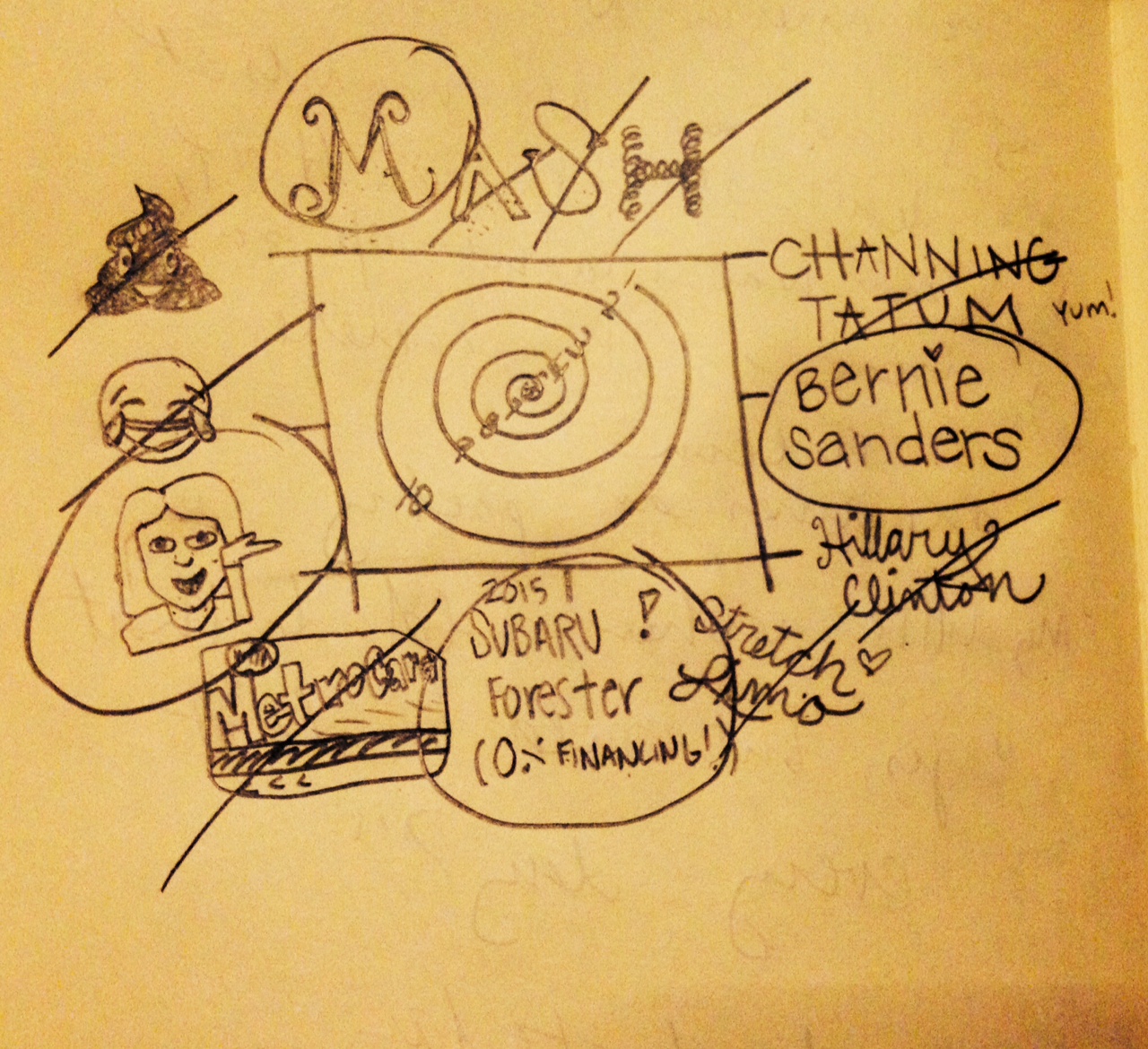

My fifth grade year, I was addicted to the game of MASH. Every day before school and at lunchtime, my friends and I would huddle around our spiral notebooks, trying our hands at rudimentary divination. Who would we marry? How many children would we have? What car would we drive? Would we end up living in mansions or shacks?

Back then, I solidly believed in the institution of marriage, and probably wanted to marry Jonathan Taylor Thomas or Elijah Wood. I wanted 2 or 3 children, though I always left that third slot open for my friend to play a wild card. More than once it was predicted that I would have 1,000 children. Wow. I'm thirty, unmarried, and childless. Better get on it.

Oh, the MASH days, before I paid attention to gas prices or the idea of keeping my privilege in check. At first I wanted a simple convertible, but the game made me greedy. Soon I was writing "Hummer stretch limo with a hot tub and a personal chef" in tiny letters on the game board. Meanwhile a friend would write in "Clown Car" as my third option. Thank you, whoever you were, for keeping it real.

I loved drawing the game board, perfectly-shaped, filling in the spaces. I loved saying "Stop!" as my friend spiraled her pencil in the middle box, sealing my fate. Maybe what I loved most of all was that, no matter what the outcome was, there was always a chance to play again, to keep playing until the perfect future appeared.

Trinity Tibe is a co-founder of Say Yes Electric Collective, an art community in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, that creates space for diverse artists and encourages collaboration. She is working on her MFA in Poetry at The New School, and she also loves to draw, paint, and puppeteer. Find her at TrinityTibe.com or @trinitytibe

For Week Three, we have scooted away from Words for Wallpaper and asked Rehani about her own relationship, attitude, and experience with the art and act of writing by hand.

HANDWRITTEN: Tell us about the current state of your handwriting. Are you happy with your penmanship?

ANDREA REHANI: Majority if not all of my writing is initially written by hand. However my penmanship isn’t great. It resembles messy 4th grade handwriting. There are times I wish I wrote like my mother. Hers, elegant cursive strokes. Before I knew I was a writer, I was a reader. I used to copy my favorite sentences from books into my journal. I have been writing in a journal since I was in third grade.

HW: What word do you use, prefer, like, or dislike, when it comes your handwriting homes, and what kinds of things do you write by hand?

AR: Sometimes, I think certain words carry certain identities, stereotypes, gender, or images. For instance diary writing is often associated with women and feelings. I like to use the word journal – I find it to be mostly neutral and it conveys thinking. I handwrite everything first: outlines, essay drafts, poetry, and grocery lists. Although, I wish my grocery lists were like haikus.

HW: When you write, poetry or prose, where do you begin and where do you end? Do you start out by hand and finish by hand? Do you revise on a computer? What do you consider a finished product to be?

AR: I start my poetry, prose, prose poetry, my in-between stage, all by hand. My essays are usually written on color-coordinated and numbered note cards. Once I have the bones of what I am working on, I transfer it to a computer. My essays undergo several drafts and once they are on a computer, I print them, cross out words, handwrite words, and revise them on a computer. I don’t like to initially revise on a computer – I miss things. I need my writing physically in my hands. The words flow more organically when I handwrite them, too. Writing is never done because my perspectives are always changing. However, when I feel like I want to set one of my essays on fire or if I feel empty, then I consider them done for the time being.

HW: Do you write handwritten letters often?

AR: I have a pen pal in Michigan and we attempt to exchange every month or so. When I lived in New York, my mother and I exchanged letters. My mother has written me letters since I was young. I have a box filled with them. She, too, starts her day writing in her journal.

HW: Where do you like to write by hand? Is place important to you, or is it something else - vibe, music, the trip to that place, or otherwise?

AR: I like to write down conversations I overhear on the train. Sometimes, they make me laugh. Sometimes, they’re absurd. Sometimes, they are profound. I like to write down things I have to do. I like to write down unfamiliar words and their definitions. I like to write down sentences or graphs or stanzas or lines I’ve admired. I like to write in parks and coffee shops. I like to be surrounded by people as I immerse myself in my writing world. I need a little noise, but I don’t like to listen to music when I write unless it’s in a coffee shop. The music there is subdued with coffee and voices.

For Week Two, we sat down a thousand miles away from Andrea Rehani and asked her about the origin, spirit, and plans for Words for Wallpaper.

HANDWRITTEN: What is the origin story of Words for Wallpaper? How did it emerge, and what was its genesis? Or, if there was a WikiHow site on your project, how many steps would there be, and what were they?

ANDREA REHANI: Words for Wallpaper branched off of the concept behind Poems While You Wait. Before I became a member, I was an enthusiastic customer. I was in a coffee shop with my sister and we were brainstorming creative writing ideas. I remember saying something like, “I want poetry to be framed like photographs.” Then, my sister came up with the name. Like Poems While You Wait, people give me random topics and then I produce an original poem. Unlike Poems While You Wait, it’s not done on the spot. Sometimes, the poem takes a few days to make.

The project is to get people excited about poetry. I don’t think you have to be a poet to enjoy a poem. I also feel personalized poems are special. It’s pretty rad to see people excited about writing – especially poetry. There’s this notion that poetry is as scary as math word problems or it needs to be something that is impossible to understand. I remember one of my first poetry classes with Kathleen and she wrote on the board, “Poetry must be as well written as prose. –Ezra Pound” I believe in this statement. Kathleen has taught me how to analyze the dramatic situation of a poem. She taught me to consider: who is speaking, to whom, and under what circumstances?

When I compose a poem, I still use those questions. I also consider form and content to communicate an image, a thought, or a memory. Form is structure; it can mean language, style, patterns, or the actual form of a poem. Content is meaning; it can mean characters, emotions, ideas, or tone.

HW: Does your project have a mission statement, or guiding phrase that governs its spiritual space?

AR: I suppose my mission for W4W is to not only get people stoked about poetry, but also make it accessible for anyone. My mother and I exchange handwritten letters and I hate how many people don’t anymore. I love getting mail - especially thoughtful letters. I have had a pen pal for two years and we exchanged handwritten letters. The mission is also to make handmade art. My favorite type of poetry is prose poetry. The poems I produce are in this form. I love writing in a hybrid genre – it’s something that still is unexpected. Paragraphs seem familiar but are tweaked in prose poetry – they alter a familiar structure.

HW: Tell us a little bit about your experiences with the project. The topics you've received, the challenges you have encountered.

AR: I started W4W by asking friends for topics. I asked readers and artists. At first I was a little nervous because I wanted to create something perfect for my friends. Then I realized there is beauty in imperfections. Creating something perfect isn’t what Words For Wallpaper is about – it’s about experimenting, understanding, and building. Like all handmade items, I want to create something unusual and unique. It’s unique to frame poetry, an image, a picture told in words.

These topics serve as writing prompts or exercises for me. I’ve written poems on topics of love, anniversary, twinkle lights, teeth, doppelganger, cacti, being in the woods at dusk, and the unknown. The hardest topics for me were love and anniversary. I knew they were gifts and they had to be extra personal. I’ve noticed personalized poems attract people. Writing is a means of communication. To gift a poem has a thoughtful intention. I want my poems to be just as thoughtful. It’s interesting to see non-poets associate thoughtfulness with poetry.

HW: Say Words for Wallpaper is a car, and its night. It has its headlights on, and so you, and us, know where it's headed, but even high beams fade like quicksand in the night. Do you have a destination in mind for Words for Wallpaper? Where is the project heading? Or, what's the next turn? Or, are you not concerned with what is beyond the bend for now?

AR: I eventually want to hand-make my own frames. One ideas includes using the hard covers of books to make a frame. Another is creating a black-out poetry frame. This would entail taking any form of writing (such as an article, poem, piece of prose, etc) and blacking out certain words to create a revised and new poem. I like the idea of a poem within a poem.

HW: Tell us about the name and how it relates to the typewriter, frames, still-words, and motion-images. Basically, tell us about the intersection between mental and physical realms of poetry, people, and expression.

AR: Wallpaper, art, typewriters, quotes are all used as a means for decoration. But, I don’t want my art to be pretty or just decorative; I want it to make you think. I like typing on a typewriter because it makes me think harder. I can’t look something up on the Internet. I have to rely on myself. Much of art is waiting. Much of writing is staring. The name is meant for decoration but there’s a duality. Decoration is associated with identity, personality, and choice. I wanted my name to encompass all of these ideas.

HW: How can someone get Words on their Wallpaper?

AR: If you are interested in a poem, send me a poem topic at WordsForWallpaper@gmail.com. I will mail you the poem.

THE IMAGES.

AND THE INSPIRATION.

When we asked Rehani about the inspiration for Words for Wallpaper, she was quick to mention Poems While You Wait, which is a group of Chicago poets who write poetry on demand (think: The Haiku Guys in NYC, only, they're not stuck to seventeen syllables). Founded by Dave Landsberger and Kathleen Rooney, you can find the traveling poets at events, street festivals, weddings, parties, or random locations around the city. For those on the receiving end, there is little to it: you see them sitting somethere, you think, I wish someone would write me a poem today, so you approach them, engage in friendly fire, fork over $5, pick a topic, and whoever is up next (they rotate), they write you a poem within 15-20 blinks. Don't a lot of people do these kinds of things? You see some individuals doing this, but rare are established groups of published poets. How will I know if it's them? Says Rehani, "They are the ones with the vintage typewriters." And she is one of "the ones." Oh, and all the proceeds go to Rose Metal Press.

One obvious connection between Poems While You Wait and Rehani's Words for Wallpaper is the typwriter. "The approach to writing on typewriter is so different than a computer," Rehani said. "There isn’t a delete button. You need to have a certain kind of confidence when you use a typewriter." What about mistakes? They are everywhere. "Sometimes, I make mistakes and then I try to make the mistake part of the poem." And how could they not be? Standing before them is their reader, audience, and judge. When that kind of presence is present, it can increase the sound of time.

"It's interesting to see where writing can go in such a short time. We, writers and poets, manipulate memories and images, but it's a little challenging when put on time constraints. It's almost like time is manipulating the poem, too."

Words for Wallpaper - Poems While You Wait

HANDLED BY HANDWRITTEN

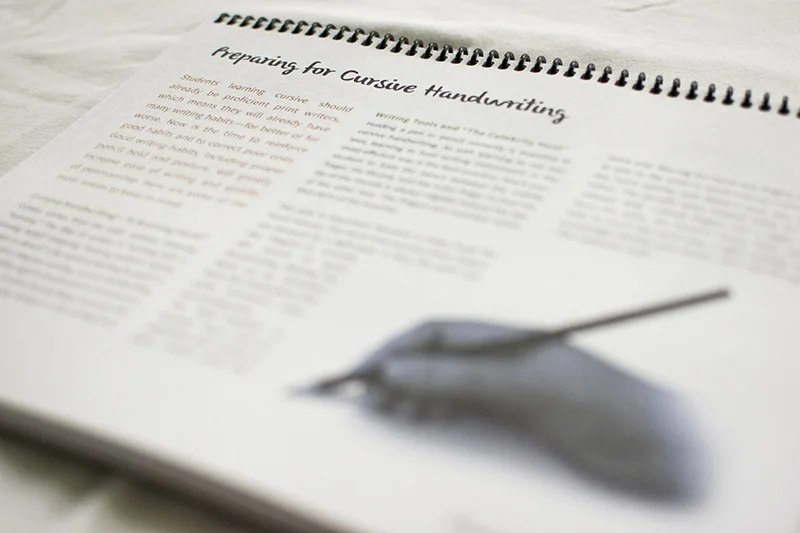

Meet Linda Shrewsbury and Prisca LeCroy, the mother-daughter team who has changed the world of cursive writing. Literally and figuratively, they have reshaped the way children, and adults, learn cursive writing: not in alphabetical order, but by shape. And in less than one week, their second campaign comes to a close. Their first, a Kickstarter last year, was successfully funded and raised $33,000.

This helped bring CursiveLogic, the workbook you see below, into existence, and now, Shrewsbury and LeCroy are set on taking it into the classroom with their new campaign, Cursive2Class.

What exactly is CursiveLogic's method? It reorders the alphabet into four shape-groups (oval, loop, swing, and mound), color-codes them with visual and audio cues, and fits into a single workbook that has — prepare yourself for this — regular paper and dry erase worksheets. Heaven, we know. Whereas old models required students to sit in place and etch the alphabet in order and silence onto recycled and photocopied sheets of paper, this four-lesson workbook takes students through each similarly-shaped group of letters, while at the same time teaching how to write full-length words. This model, workbook, and business is the absolute example of how, coupled with new technologies, we are finding more effective ways of teaching children the fundamental skills and knowledge necessary for cognitive development.

This is the answer the core curriculum has been waiting for, not to mention Town Hall Meetings and online forums. Cursive writing has been disappearing from the classrooms, but that is because the way it was being taught had not changed with the ways in which students are learning, and expected to learn, in the twenty-first century. We are preparing students for jobs that don't exist yet because we are still inventing them. But the thing most people don't see is that when cursive handwriting goes, a lot of other things we cannot see or feel vanish with it as well, including reading comprehension, articulation, writing and sensory motor skills.

The old model wasn't working. We live in a technological world, and one that is constantly changing, which means we have to change with it. And CursiveLogic is not just keeping up, but it is ahead of the curve: they have side-stepped the political impasse and built their own business, a patent-pending approach, in fact, and instead of arguing back and forth with adults, they were sitting down with students and watching them work. Ever since their model surfaced, they have been gaining support from handwriting experts, educators, politicians, psychologists, and scientists around the country.

You might be thinking, this looks great, but not for me. We understand not everyone will want to relearn cursive writing, though we actually encourage you to do so (we have bought their workbooks and are going through it ourselves), but there is still something you can do: spread the word, sponsor a workbook, and help CursiveLogic make its way into the classroom. Join us and participate in their Indiegogo Campaign. We selected the "Get One and Give One" option, which we recommend, but if you want to Give Two, then do your thing.

The next time you hear someone up in arms about cursive writing, you can pat them on the shoulder, hold the cursive book you bring with you everywhere just in case you feel the urge to loop or swirl, and say, "You can stop cursing at cursive writing now."

Follow the links below to help support the remaining days of their campaign (Cursive2Class) and help a kid. Spread the love by liking them on Facebook, and check out their story in their words.

Sociologist and Professor, Michelle Janning

I never really know why I do it, but there I will be on various afternoons throughout the year, sitting on the wooden floor in front of my closet, peeling tape off a slightly battered box. On the top flap of this box is two words in uppercase letters and permanent pen: DEEP STORAGE.

I've come across a lot of people who have the same — a box or ten of memories sitting on closet shelves — and people who do the same: thumb through this deep storage from time to time. The effects are not always the same, as the very reason for the impulse to sift through the past can vary, but there can often be a combination of emotions —nostalgia mixed with regret, or warmth mixed with emptiness. Albeit peripherally, I think it might have something to do with what Adam Phillips explores in Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life, where there can be a strong sense of constant reflection: wondering what was, what could have been, and what could be. But I also think quickly to Joan Didion's "On Keeping a Notebook," which speaks to the importance of recording life and keeping a close proximity to the past.

One item that many seem to hold onto are letters of past love. But why do we keep a hold of these romantic reminders, especially of ones long gone? We found an inkling of an answer in an article recently, "Why Love Letters Matter, Even After You Break Up." It features words by sociologist Michelle Janning, who happens to be a professor at the college I attended, Whitman College. A lot of her research has looked at concepts of "betweenness," and romantic correspondence surely qualifies as that. But she has also looked at another intersection: the differences between digital vs. handwritten romantic correspondence. When asked why we hold onto these records of our romantic past, Janning replies: "They represent who we were, which is part of who we are. They become our relationship counselors, reminding us of what to avoid in future relationships and what to rekindle."

We recently spoke with Janning about her research and work, but also about her own experience and relationship to her deep storages and handwriting.

BRETT RAWSON: What led you to studying the divide between handwritten vs. digital correspondence in romantic relationships?

MICHELLE JANNING: I was cleaning out a closet and found the box of letters I'd stored from high school and college. After reading through them I talked with my husband, and we (college grads in the mid-90s just after email started and just before the internet) figured we might be the last generation of letter writers. Then lunch with friends of different generations (one who had a folder in her phone labeled "texts from cute boys") made me wonder further. Full story in the publication attached.

RAWSON: What did you find from your study that you didn't expect? Did anything surprise you, did new patterns emerge, did you find any contradictions between what people say and what they do? If you were to extend this research, what would be next?

JANNING: The most surprising thing I found was that, while women are more likely to save letters and mementos from relationships than men (and to save more of them), men tend to look at or "visit" their saved love letters more frequently than women. And men tend to store them in more accessible places (as opposed to closets, under the bed, or in storage).

Some of this may be because women tend to be tasked with household organization more, and spend more time than men on creating a storage location that is decorated or made special in some way. Right now I'm trying to figure out if it'd be worth studying the data to look at generational difference. The hard task here is that technologies change so fast that I'm not sure I can capture both age differences and technological change simultaneously (because change in one can falsely suggest change in the other).

My big project now is writing a book that uncovers how the objects and spaces in our homes tell us something about family relationships. Love letter storage will be part of the chapter on dating, sex, and paths to family formation.

RAWSON: Between-ness seems central to your focus. Aside from technology, what else comes in between us and handwriting?

JANNING: Good question. For me, between-ness is about internal conversation when I find myself unable to agree with polarized claims. Relating this to handwriting means that I am neither a huge fan nor critic of handwriting. I can see the importance of keeping it in order to foster all the good things that can stem from it (like the aesthetic, the handcrafted, the thoughtfulness, the non-reliance on non-human technologies).

But I also shy away from romanticizing anything that hearkens back to a fictitious past when our present (privileged) perception is that it was somehow better then than now. This is true when I think of gender roles, intergenerational relations, religion, or even medicine.

RAWSON: What is your own experience with handwriting?

JANNING: My dad had a brain tumor after college but before I was born that rendered him physically disabled such that he lost hearing in one ear, had partial paralysis in his face, and had to switch hands for writing. He had grown up ambidextrous. I have vivid memories of watching him sign his name with the most bizarre pen strokes, which took an inordinately long time, but which never seemed to make me feel impatient.

This matters because I am an impatient person. I also have looked at his musical compositions from college (he was a music major), which were all handwritten. Since the pre-tumor writing was different from what I saw him do, I always thought about his life as having two segments. Only now do I think that maybe the visual representation of his handwriting may have had something to do with that perception. Add to this the fact that my mother has handwriting that is like a flawless art piece, and no wonder I'm intrigued.

I learned calligraphy as a 10-year-old, and taught my son to do it when he was younger. I love examining how the aesthetic world can tell us something about human relations. I have always spent time shopping for interesting pens, inks, and papers, especially when we'd stay with cousins in Germany as a child. In high school and college, I would pride myself on the clever use of colored ink to help with anything from chemical compounds to calculus formulas, and from maps to poems. I recently was asked to write a book review for an academic journal, and I decided to hand-write both the notes and initial draft. I did this because I bought a new fountain pen in Germany this summer. The final draft (which was then crafted on the computer) went more quickly than anything I've ever written, and it was accepted without a single revision (complete with both a formal and informal note from the editors telling me how amazing it was).

RAWSON: Are you concerned that handwriting / cursive lessons are being eclipsed by keyboard proficiency lessons in the U.S. school system?

JANNING: Yes and no. I see the use of keyboarding as necessary for the work that my students do in college, and that it is most certainly an efficient way for me to do my own writing. (Again, I'm impatient). But because I find myself grateful that my son was on the cusp of cursive instruction (he received some in Denmark when we lived there, he did a little in 3rd grade just before the school moved to a greater focus on Chromebook instruction), I must think it's a good thing.

My bigger concern with the Chromebooks has more to do with the increase in standardized testing, which I presume may be exacerbated by virtue of the fact that students are getting quicker at keyboarding. This makes testing more efficient. What I liked about my son's teachers last year was that, especially in writing (Hooray for Mrs. Hartford!), the kids would draft things by hand, learn to navigate and edit on a computer, and be allowed lots of time for crafting stories. So, as far as the creative writing process goes, I think his teacher struck a good balance.

Other than the aesthetic coolness of nice handwriting, I am concerned that students will not be able to READ handwriting, which limits our ability to learn things from historical texts.

RAWSON: When you think of your own handwritten correspondences, what comes to mind?

JANNING: How little I do this. I am not a letter writer. I think of little notes to my son, or drafting my writing by hand. That's funny I suppose.

RAWSON: Phenomenologists have argued that the self falls away when we are engaged in an intense activity, usually one that collapses the sense of the mind-body split by activating both elements. Do you think the writing implement of choice could act as a bodily extension, and that writing by hand helps combine subject and object in ways that promote intimacy with a text, whereas typing into a word document promotes separateness of subject and object?

JANNING: I am not sure, because I have felt precisely this way while crafting my writing on a computer screen. For my aging body, the times when I am most likely to feel the mind-body split is when I am in pain. For typing, it's in my shoulder and my eyes. For handwriting, it's in my wrist.

A letter from mother to son during World War II illustrates the tense and tender sides of war, and long-distance correspondence.

Read More

BY HANDWRITTEN

We recently came across Shit Rough Drafts by comedian Paul Laudiero. After reading through it in one sitting, we spent the next few days losing our marbles. Laudiero's humor is magnetic, often departing as quickly as it arrived, leaving us to enjoy his imaginary musings on the greatest works, shows, and plays of our times.

Chances are, you have experienced several of the 135 books, movies, and TV shows that appear within Shit Rough Drafts. While that'll enhance the experience, it doesn't exclude entertainment. You don't need to have read Eat, Pray, Love to deeply enjoy Laudiero's title-twists.

Shit Rough Drafts exposes process, and in the process, pokes fun at finished products. How do these "must-reads" make their way into the world, and did they ever take a different shape? Are those who we hoist high out of reach just as messy, confused, and lost as we are?

We spoke with Laudiero one early morning while he was strolling alongside Central Park, coffee cup in hand. It was eight in the morning. He was alert and awake, while we were on a porch shielding our eyes from the early morning sun. We told him about Handwritten, and how we wanted to keep the humor in handwriting. He said that was good, because a site like ours would bore people to death. We totally agreed.

Shit Rough Drafts is a new wave of coffee table books. In that, it isn't idle. The book is impossible to not pick up, and difficult to put down. It's not easy then to pick our favorites, but since we had to, here are three that kept us laughing well into a deep sleep:

In this micro-ritual, Ali Osworth lays out the key ingredients to safeguarding ink's elegance, and her daily quest for grace. For those of you looking to slow down your mornings, taking a look at what's on your desk is a good place to start.

Read More

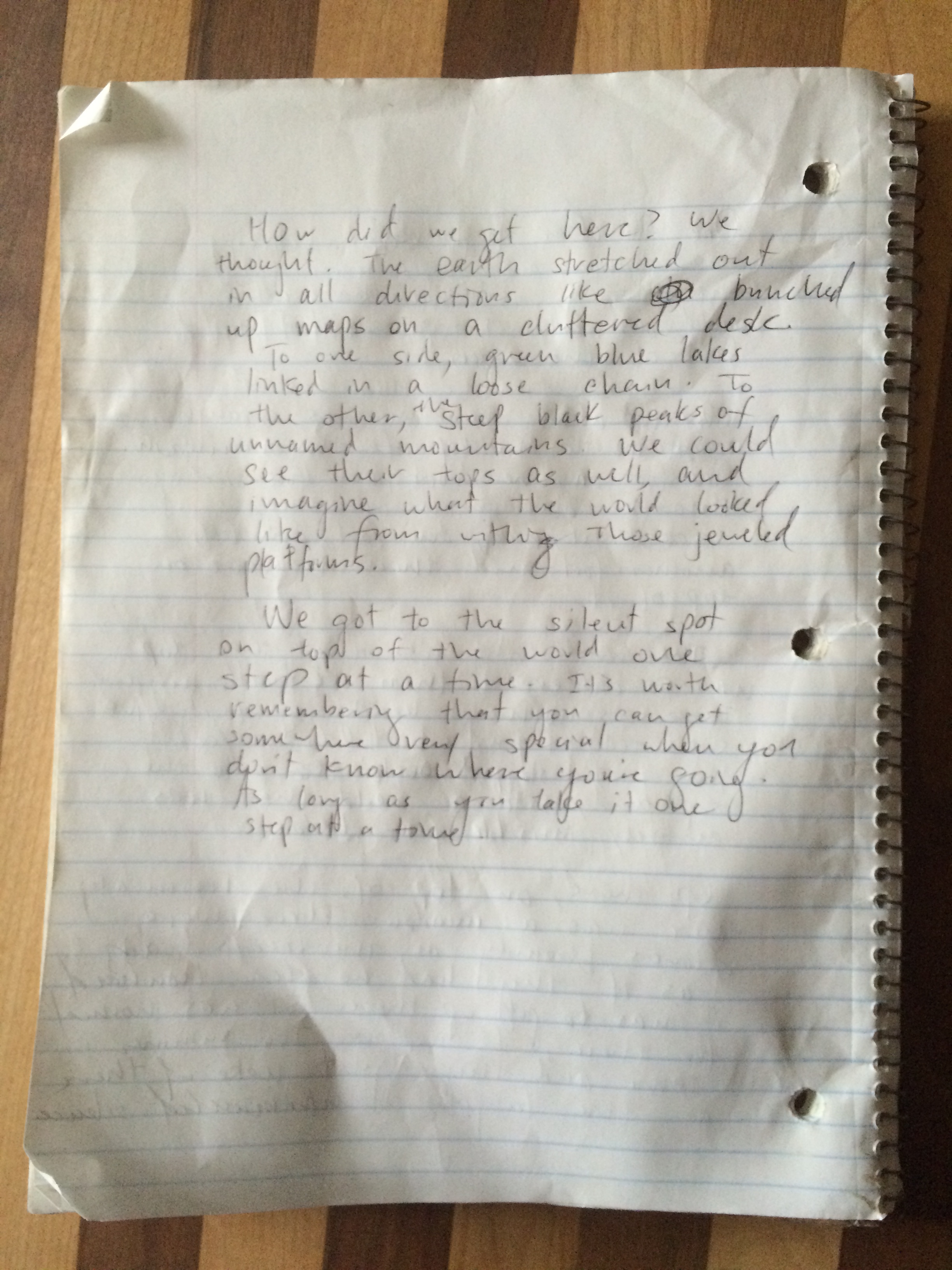

On the top of a mountain in the Pacific Northwest, author Chad Frisk came to a clearing. He didn't expect to write there, but he also didn't expect to be there, which is exactly why he wrote there. Below is the result in its original shape.

“The top wasn’t what we thought it would be. There were no signs telling us what to expect. You just stepped up and into a world that was entirely invisible from below.”

“How did we get here? we thought. The earth stretched out in all directions like bunched up maps on a cluttered desk. To one side, bright blue lakes linked in a loose chain. To the other, the steep black peaks of unnamed mountains.”

Sometimes, words do not express the thoughts in the shape that we feel them. For Brett Rawson, he often finds himself in need of blank space, a pen, and his hand to fully follow the shape of his thoughts.

Read MoreA writer reflects on his first experience with a journal, which happened to coincide with living away for the first time as well, at the age of 26.

Read MoreA project that weaves together generations, experiences, and handwritten expressions.

Read MoreIs the notebook half-empty or half-full? In this essay, Joyce Chen sets out to test and trust her hand, a routine tethered to time, with the hopes of avoiding the pitfalls of resolutions by resolving to reflect. Are you up for the screen test?

Read More

BY CHAD FRISK

I don’t know about you, but my mind is a disaster. Things are constantly whizzing through and then clogging it up. Things proliferate and congregate, ideally like constellations in the sky but typically like commuters during rush-hour. It’s a mess. Writing is, as I see it, the process of making that mess suitable for display. I learned the hard way that there is an appropriate tool for each step. I wrote the draft of my first novel by hand. I thought it would be cool. It was actually very dumb.

I filled fifteen notebooks. I went through a dozen erasers. Oftentimes I chose not to revise because it would be too much of a pain to cross things out and scribble in the margins. When I finished, I typed the whole thing into a Word document anyway, one indecipherable page at a time from tiny, gold-tooled notebooks that refused to stay open on their own.

I didn't know what it was about when I started writing. One day, I walked past an old, abandoned clock shop and thought it would be interesting to write a book about time travel. That was my only idea. I bought a notebook, scoured my apartment for a pencil, and started writing.

I was living in Japan at the time, working at a junior high school as an assistant teacher. That year, I didn't have anything to do. It was my job to go to four hours of class a day and read from a textbook. The other four hours were my own.

I decided to write a book. When it was finished, it had nothing to do with time travel. In fact, it had very little to do with anything. It was four or five stories posing unconvincingly as one, scrawled across 100 Yen notebooks I purchased at convenience stores.

There was a psychiatrist. He was frustrated by his patients' lack of progress, and decided to pursue alternative therapy - which included breaking and entering, kidnapping, stalking, and mild psychological assault. There was a burned-out business man. He was so deep in self-help that he had lost sight of how good he already was. There was a server at a nightclub for the uber rich. She was tired of getting hit on by three-piece suits, but was making so much money that she had convinced herself it didn't matter. There was a ten-year old boy. His grandpa had died, leaving a hole in his after-school routine that he didn't know how to fill.

There were others. There was a detective possessed by the ghost of Dick Tracy, an old illusionist whose understanding and lifelong exploitation of cognitive biases had poisoned his view of humanity, and a girl who lived in a castle with a mother and father who didn't pay attention to her. There was also a beanstalk, a ruined city, and a sleeping giant.

It needed an almost complete overhaul. To do that, I abandoned my pencil for a keyboard. Computers are amazing because they make editing incredibly easy. Point, click, drag, delete. Done. It’s infinitely easier to revise already written words on a computer than on a pad of paper.

It took me about eight months to handwrite the first draft. I spent nearly an additional year revising it. I cringed while rereading my notebooks. The story didn't make any sense. Who were the characters? What did they want? How were they connected? What was the point?

From the flurry of keystrokes, slowly, something that could be called a narrative emerged. I knew that it wasn't good enough, but I tried to get it published anyway. After a half dozen rejection letters (and at least as many unreturned emails) I gave up.

But I had something. It was all thanks to the computer. Revising the original text by hand would have been impossible.

But I'm glad I started with pencil and paper.

Handwriting is good because it can go all over the place. Impulse is where my writing starts, and it’s easier to transcribe impulse with a pen than a keyboard. I can scribble, doodle, draw lines, cross things out, and generally be very messy. Out of this mess emerges something coherent enough to take to a laptop.

The process of refining continues digitally, because that’s what bits are good for. I find that the first step in mining my mind, however, is often best performed by hand.

Chad Frisk is a graduate student at the University of Washington working towards a Masters in Teaching English to Students of Other Languages. His books include Direct Translation Impossible: Tales from the Land of the Rising Sun, which was published in October of 2014; a Japanese version of the same to be published in March of this year; and and he's working on his next book - this time entirely on a computer. His website is nobodyelsewillpublishme.com.

His grandfather hadn't been to a bar in forty-seven years. An interesting details until his grandfather reveals another forty-seven year secret - one that was kept from him, and now kept from others.

Read More

BY SARAH MADGES

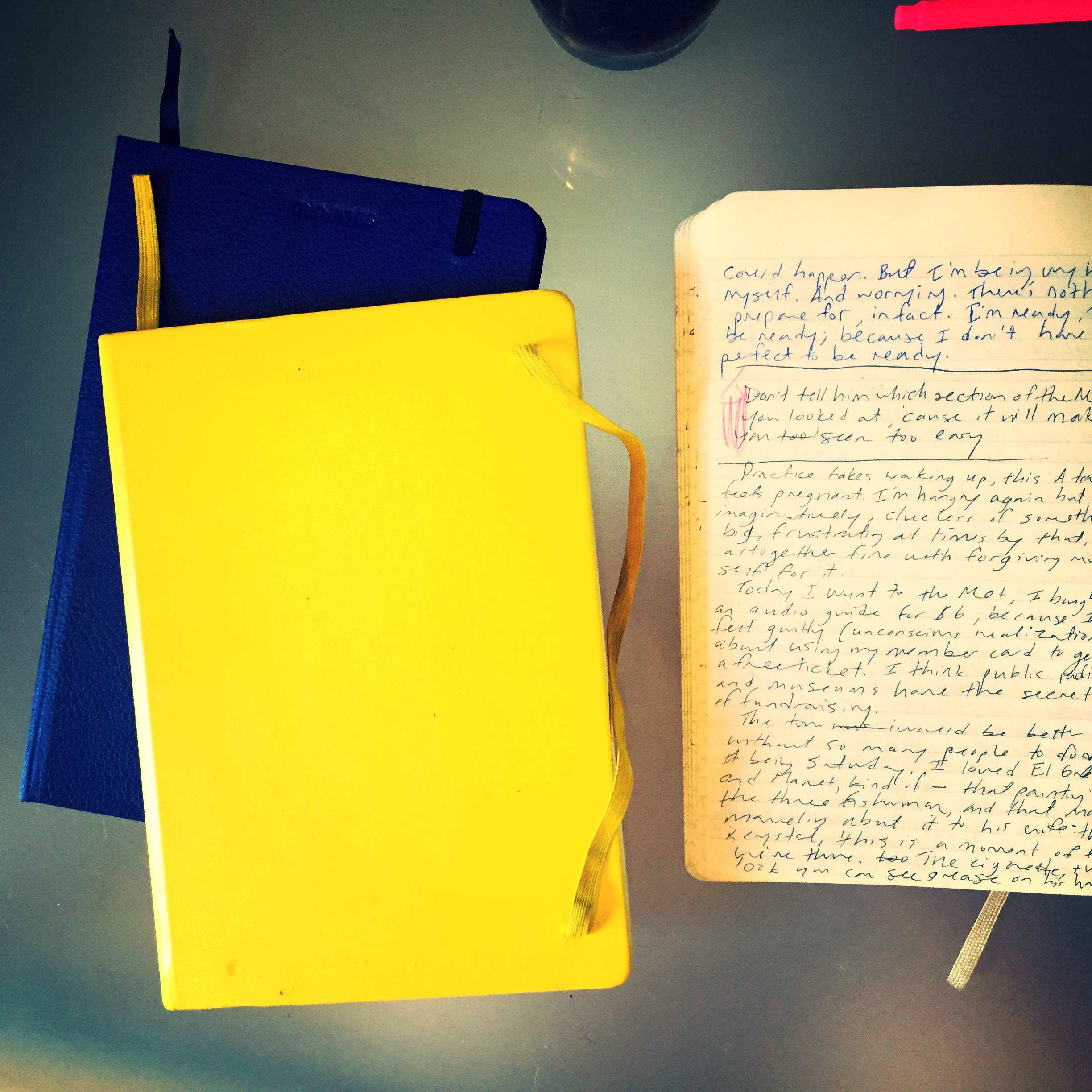

I am often asked, “What are you going to do with all of those?” in regards to my ever-amassing collection of notebooks.

The tone people adopt when they ask me registers as an accusation, or a warning that they’re going to turn me in to the reality show Hoarders’ producers and stage a televised intervention. True, the amount of notebooks I’ve accumulated makes moving daunting (the journals, both blank and filled-in, take up at least four standard file boxes, and are heavy). But these bound batches of scribbles mean the world to me. Because it isn’t just the words that matter — the content ranging from teen angst to amateur poetry to higher ed revelations — but the format. The tangibility. The way the words look on the page. The way my handwriting sometimes forms tight serpentine ribbons or grows looser and larger when tipsy or tired or both.

The materials matter; even the notebook choice tells a story. Moving chronologically, my notebooks upgrade in quality from flimsy composition notebooks (Harriet the Spy-grade Meads) or one-subject college ruled notebooks I also used for high school Trig, to those ubiquitous ribboned moleskines, or Germany’s analogue, the Leuchtturm, or even the notebook in which I composed this draft—a Stamford Notebook Co. lizard embossed cobalt beauty handbound in England.

The medium change means a few things: 1) I moved up one ladder rung in the service industry and could afford nicer products, 2) I was starting to take myself seriously as a writer, and each double-digit-$ notebook was an investment in that continued pursuit 3) other people were taking me seriously as a writer, and gifting me nice notebooks for holidays 4) I realized the paper quality, brightness, and thickness, all contributed to the actual look of the text.

I began to appreciate the aesthetic of each individual journal entry, independent of the actual written content.

BY BRETT RAWSON

As a kid, I preferred to cruise in crowds and tell stories in front of audiences. I didn't like to read or write. By eighth grade, I had left both far behind: my reading and writing levels were three years behind me. I remember my mother used to turn on the microwave timer for thirty minutes, pleading me to read, if not just look at, any book. I'd say of course, she'd walk away, and fifteen minutes later, I'd approach the microwave, and press five buttons one second apart, mimicking the end of the thirty minute session, and with not so much as a be back later, I'd be running down the street toward a cul-de-sac of activity.

But in between two rice paddies, around the age of twenty two, I discovered the wild noise and absurd worlds that existed inside me. By simply putting thoughts to paper, new universes of ideas came flowing forth. Each night, as I sank into these stories, I found a sense of relief in a new kind of silence: writing by hand. In the beginning, most were about the everyday, but I recall many faraway thoughts. I ran after each, even if it meant brushing up against a vanishing point. I didn't always make it back to where I began, but I also realized that wasn't the point. I was supposed to be, or perhaps get, lost.

A decade later, my closet is the only one complaining about my now daily practice. The process itself is about processing, and during stretches of time when I am not handwriting enough, I feel the difference in my mind. The distraction, echoes, and pressures. They build up if I don't clean things out. There is continuity is all the connections: these kraft brown journals. I have a few that exhibit some decorations, but those are specifically journals I keep to write about writing. When I open up these covers, I walk inside an open. And in that undisclosed place, nothing has to make sense.

Didn't we just discover a new planet? We're always discovering new planets. My telescope is just pointed in a different direction.