I Have No Choice But to Revise • Keith Baldwin

Bretty Rawson

WRITTEN BY KEITH BALDWIN

My handwriting is fucked. The penmanship is not as illegible as some, but in terms of how I physically write by hand, it’s all messed up. I hold a pen against my ring finger, like the wrong half of a pair of chopsticks, and form a lot of my letters from the bottom up, rather than the top down.

When I was eleven, my dad finally noticed the issue and approached it with all the vigor and care he’d applied to the insufficient knots in my shoes a few years earlier — just enough to make me feel shitty about it, without solving anything.

He spent a few frustrated hours with me at the kitchen table, correcting the way I formed a handful of letters and the number nine. There was no progress at all toward fixing my wonky grip, which was already too ingrained to be altered so easily.

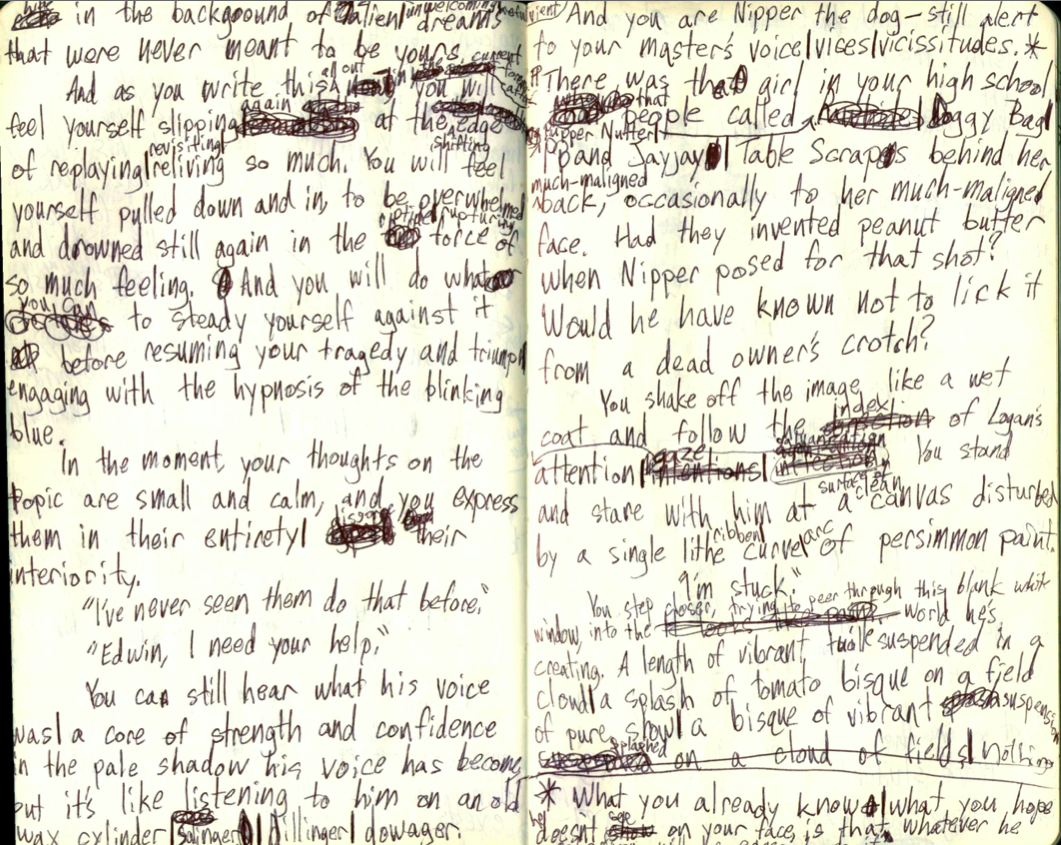

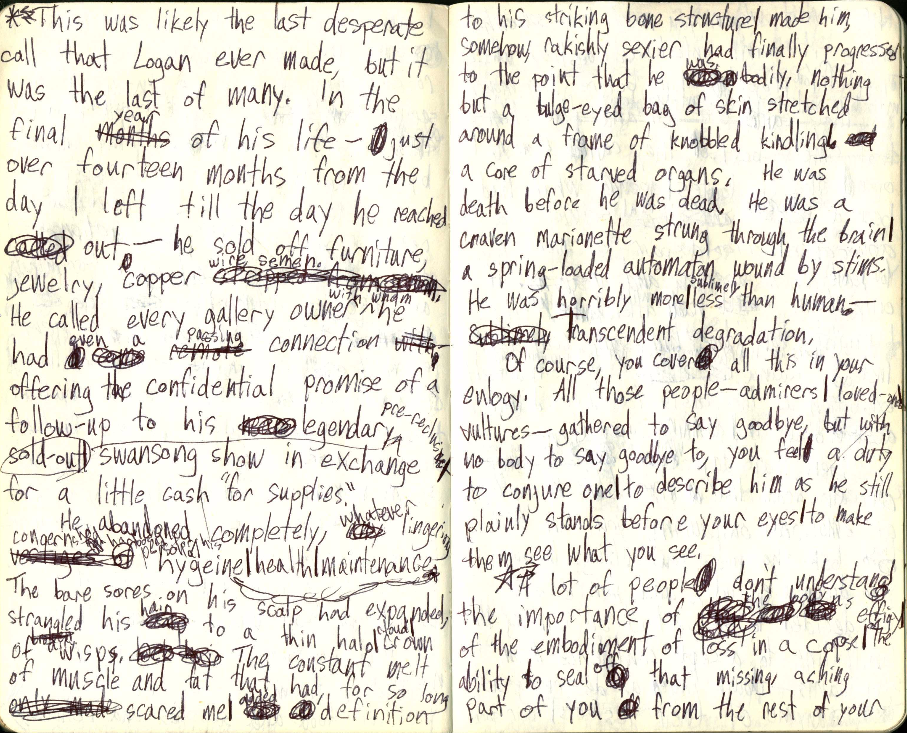

The upshot is that I don’t have the natural flow with a pen that other handwriting advocates rhapsodize. It’s always a slog for me. If I try to write too quickly, my hand and wrist start to cramp up, so my thoughts always remains three steps ahead of my pen. And while I work to close the gap, my mind is free to become distracted by flaws and omissions in what I’ve already written, leading to aggressive cross-outs and a morass of cramped footnotes that nest and crawl across margins — to be inserted in the main text later.

This would be enough to make a mess of my notebook, but on top of all that — rather than keeping everything in sequence — I have a bad habit of opening to a random blank page whenever I want to make a note, or a list, or play a game of hangman. In the middle of writing an extended scene of fiction, I will often turn the page to find story notes, shopping lists, and broken sentences for my ESL students to practice correcting. Typing up my work becomes a tedious chore of deciphering and reconstructing, tracking down where the story picks up when it’s suddenly interrupted by a sketch of my cat as an astronaut. It is almost as big a pain in the ass to work through it as it is for me to scrawl it out in the first place. So why do I even bother? Why do I keep returning to pen and ink whenever I’m writing something I care about? (You should see the rough draft of this essay…)

I know there are a lot of answers involving the way the brain works in different contexts, and how I formed these writing habits when all I could do on a keyboard was hunt and peck — and blah blah blah, a hundred other reasons why this website exists and longhand is the best. But I think the biggest factor for me is the same one that made me so much less anxious about sharing this mess of pages than I would have been about submitting something more polished. Because no one could ever confuse the contents of my notebook for a finished product — not even me.

On the one hand, this means that I can’t be held accountable for the contents, which frees me to be a little wilder in my first stab at a project. But it also means that I can’t avoid the work that still needs to be done. I have no choice but to revise.

My feelings about revision are pretty much the same as my feelings about flossing — I know I should do it, but it makes my gums bleed. And when my words are neatly typed and double-spaced, with numbered pages and no evidence of the disordered mind that composed them, I have to work to remind myself that it’s still a work in progress — that I can and should question every decision those collected words represent.

The process of transferring from the page to the screen forces me to consider every sentence with a critical eye while I retrace the whole erratic path. And I can’t even procrastinate for too long because, while a few days’ distance can bring fresh insights, a few weeks is liable to leave me incapable of piecing the whole mess together again. (It’s happened. It’s infuriating.)

I know that, for other people, writing by hand makes the whole process smoother. For me, it’s about making myself work harder, and getting better results for the effort.

Keith Baldwin is a writer and tutor living in subterranean Brooklyn while paying exorbitant tuition in Manhattan. He is sometimes worried that he might be one of those lizard people you hear about.