Dan Flavin's Art & Life • A Conversation with Tiffany Bell

Bretty Rawson

SARAH MADGES: How did you get involved with this project?

TIFFANY BELL: I got a call from Mary [Savig] because she noticed my work on the Dan Flavin catalogue raisonné. I make use of the archives on a regular basis and so she asked if I would write about one of Flavin's letters that they had because his writing is so unique.

MADGES: How did you decide which letter to talk about?

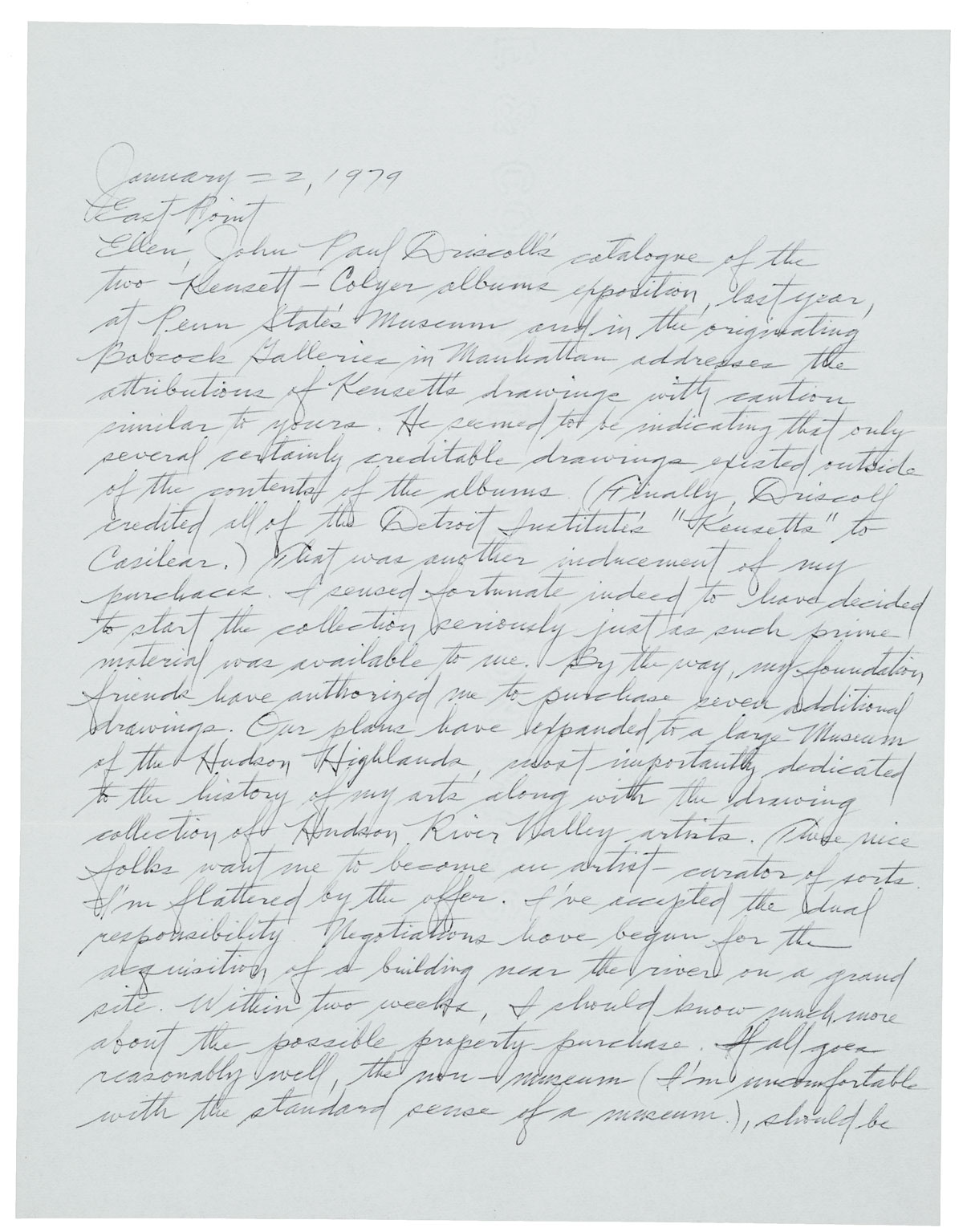

BELL: She [Savig] asked me to choose one and I was already familiar with this one because it was available online. I was also interested in it because the content of the letter reflected his handwriting. It describes his interest in 19th century drawings and landscape art, and Ellen [Ellen Johnson, the letter's recipient] had a collection of these John Frederick Kensett drawings.

His handwriting is quite formal considering how innovative his art is. It was interesting to me that it looked so perfect, exactly the way it had been taught to him.

I also knew the artist and knew he took writing seriously; he took serious care...I think he had some idea his letters would be studied at some point. He was interested in the collected writings of Cezanne and would use some of them in lectures. He was very interested in traditional writing like that, capturing the artist's life, and so I thought this letter projected that aspect of his personality.

MADGES: Why do you think archives should be public access? Why are these letters, these archival documents, important?

BELL: It’s invaluable for the kind of research I do. I think archives should absolutely be public access--and there is so much online now, which is so exciting. Even the postmarks on letters tell you where the artist was on a certain date. It’s invaluable for putting together someone’s biography.

But now, with all of these emails exchanged instead--I don't know if or how they will be saved. The quantity of material might be overwhelming to sift through. A lot was done through phone calls, so a lot has been lost there too. My work on Agnes Martin — although not entirely relevant to this conversation — her letters in the Archives of American Art are completely essential as far as learning who people in her circle were, what she thought about her art, and where she would show it. There's no other way to find this information out because she didn't keep a record of anything. Flavin kept his stuff as a record, knowing; he was prepared for people to access his writing.

MADGES: You noted in your essay that Flavin’s art resisted associations with the handmade, and yet he took such care with his penmanship. What were his journal entries like compared to his letters? You said that his letters were copied from what he wrote in his journal--did you notice any edits made between first and second draft?

BELL: His final page has no crossouts, and his letters were often typed. There are more crossouts and edits in his journals. You can really see him working through a thought.

MADGES: A kind of related question here, but what did you learn or what do you think others could learn about Dan Flavin from studying his letters that you couldn’t from biographical record?

BELL: Access to letters gives access and insight into thinking. You get to see how he presents himself to people.

MADGES: Did he write for the duration of his career?

BELL: He started in the 60s--the journals begin in 1961 or ‘62 and he kept them going through the 80s. As a young artist he was very interested in recording what he was doing as an artist. Early letters reach out to people who might be interested in buying or showing his work. I think he already knew Ellen Johnson when he wrote to her--when Flavin made his fluorescent light works they were always untitled, but were often dedicated to people. One of them was dedicated to Ellen Johnson.

MADGES: How do you feel about the fact that the U.S. Core Curriculum no longer requires handwriting instruction?

BELL: I was shocked. I even feel sorrow because I type so much now and I very much miss the way writing by hand connects you to your thought in a different way. When you actually write something down it enhances your ability to think through the idea. The fact that handwriting is slower means you stay with the thought longer.

It’s concerning that kids growing up today might not be able to read letters, read these manuscripts. Flavin’s early text is so difficult to read, you almost feel shut out. He has all these flourishes, especially the way he ends a word. It’s very sad when this kind of information becomes inaccessible.

MADGES: How did working on this project inform or change how you think about handwriting?

BELL: Well first of all, the book is really beautiful. I’m very pleased to be a part of it. It didn’t change how I think, but maybe it reinforced the idea of how wonderful handwritten letters are. Dan Flavin himself understood the beauty and great capacity of what you could convey in a handwritten letter. It’s interesting to look closely at them; you get more sense of personality, occasionally some humor. You can observe how he puts the date and place in each entry and fills the whole page, leaving no margins. He has this very meticulous handwriting that looks angular, even stylized, and always on unlined paper.

MADGES: Do you consider handwriting visual art, writing, or some combination?

BELL: For Flavin, I think it’s a lot like his drawings in some way. He used to carry a notebook around with him all the time and he would use the same pen to sketch. He collected drawings, like he mentioned in the letter: Kensett pieces. Kensett also did ink drawings on paper, often with little notes about where they were drawn and when. Flavin kind of took after him--he recorded the date and time. You can sense the connection to his past art, its influence on him.